(For my introductory overview of the Venice Biennale, please read my previous article Venice Art Biennale 2024, Part 1: The Big Picture here.)

The Arsenale, made up of the International Exhibition and 23 National Participations, was housed in a series of huge old industrial buildings on the north side of the Venice island. It was an exciting and varied show to visit, filled with thousands of artworks from all over the world. Here’s an insight into those I admired the most.

International Exhibition

The Italians Everywhere room of the Nucleo Storico (historical) section of the International Exhibition featured works by 40 artists and displayed art from Italy’s global diaspora.

The Biennale’s curator this year, Adriano Pedrosa, is the director of the Museum of Modern Art São Paolo (MASP) in Brazil. Here, the Brazilian-Italian Lina Bo Bardi’s (1914-1992) innovative display technique is used. Paintings are hung on glass panels lined up throughout the room, not on the walls, and the artworks’ captions are placed on their backs. Pedrosa chose to replicate this in the Italians Everywhere room at the Biennale.

Through this, our first encounter with the piece is not hindered by author, date, title or contextualisation details. Instead, it is more pure and personal. We are invited to stroll through this forest of artworks at our own leisure, letting them speak for themselves, without the restrictions of a conventional display. I found it a liberating experience.

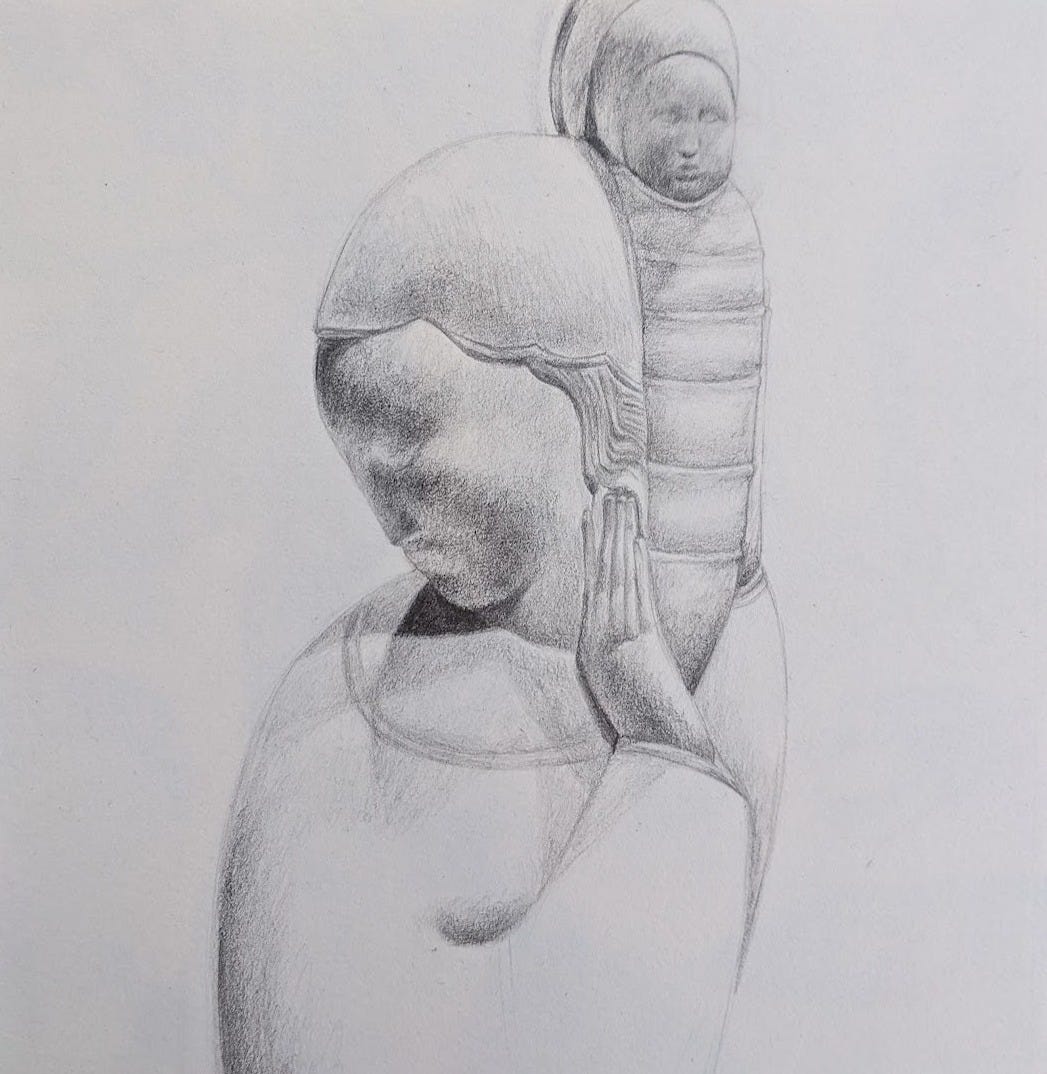

My favourite work from Italians Everywhere was a sculpture by Victor Brecheret (1894-1955) called Vierge à l’enfant. Here, the artist combines a traditional material (marble) and religious subject (Virgin and child) with the aesthetics of modern Brazilian art. Using rounded forms and subtle edges, he conveys the scene with great tenderness and affection. The smooth and unblemished white marble could have easily seemed like a cold material. Instead, the simple warmth of the mother’s embrace for her child (despite the fact that she looks away from him) was so compelling that I also felt touched by the love of the Mother of God.

Also at the International Exhibition was the Nucleo Contemporaneo section, showing works by contemporary artists, with a focus on those who are queer artists, outsider artists* or indigenous artists.

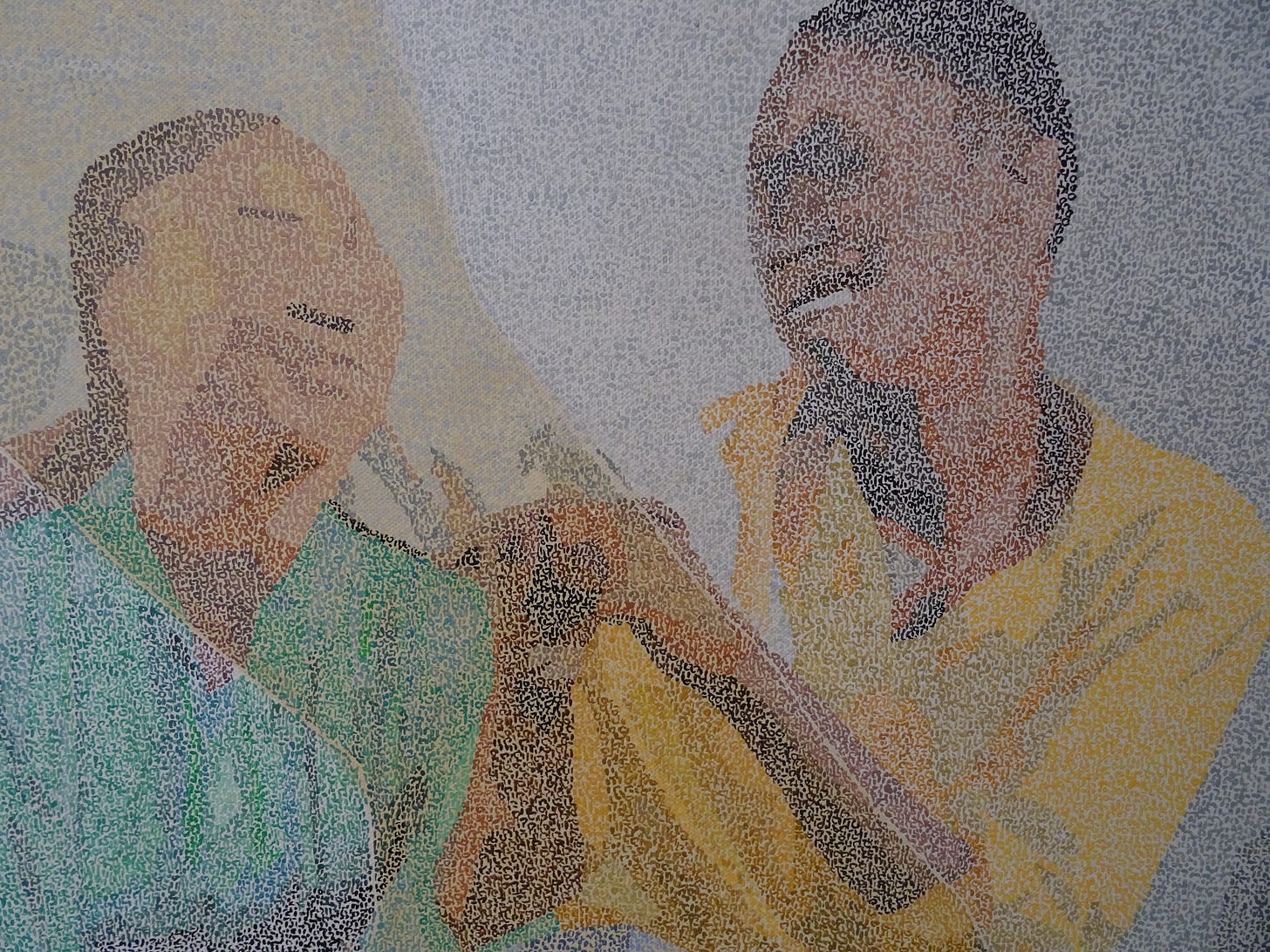

Omar Misman (born 1986) is a Lebanese artist whose series Studies in Mosaics included some of the most thought-provoking pieces in this section. These works, such as Parting Scene (with Ahmad, Firas, Mostafa, Yahya, Mosaab), depict individuals protecting ancient mosaics during Syria’s civil war. Aided by the traditional mosaic technique, Misman presents the figures as heroic. Interestingly, he provides their first names but censors their faces. This pixellation gives anonymity and references our contemporary digital world. However, the piece is not digitally but physically present and its intricacies lend it a tactile nature. I felt compelled to touch the mosaic in front of me and step into the work to protect the one inside it.

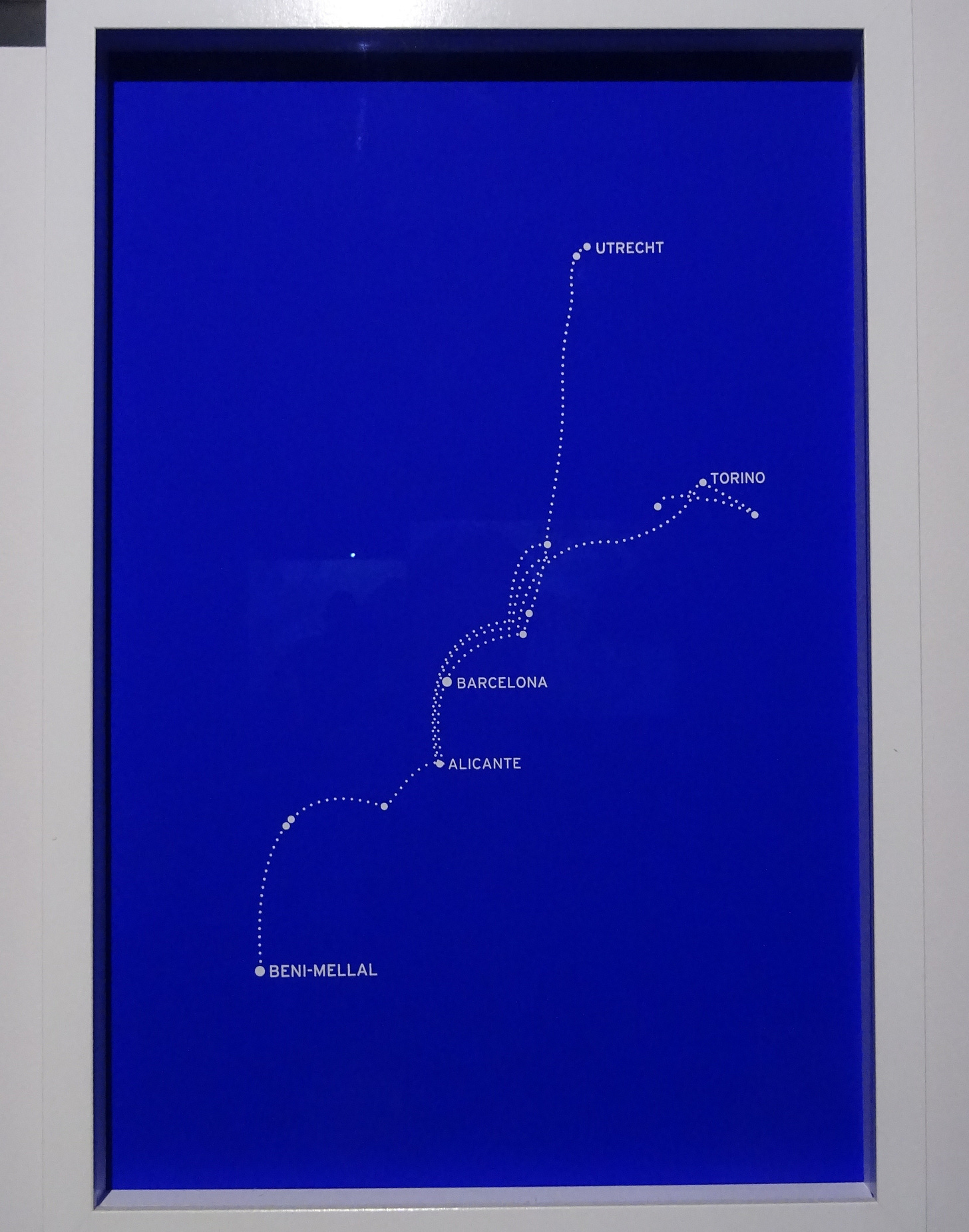

The Mapping Journey Project by Bouchra Khalili (born 1975) was a series of videos showing Mediterranean migration routes. Each video is made up of one long static shot, showing the refugee’s hand drawing their journey, alongside their verbal description of it. Khalili’s practice doesn’t involve interviews but long periods of listening to refugees and stateless citizens from North and Eastern Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia. As such, these collaborators are in control of their own narrative. The simple aesthetics and matter of fact nature of the accounts made the videos very compelling, I was completely absorbed by them. In accompaniment, in The Constellation Series, Khalili transforms the routes into star constellations, a poetic and moving response to such treacherous journeys.

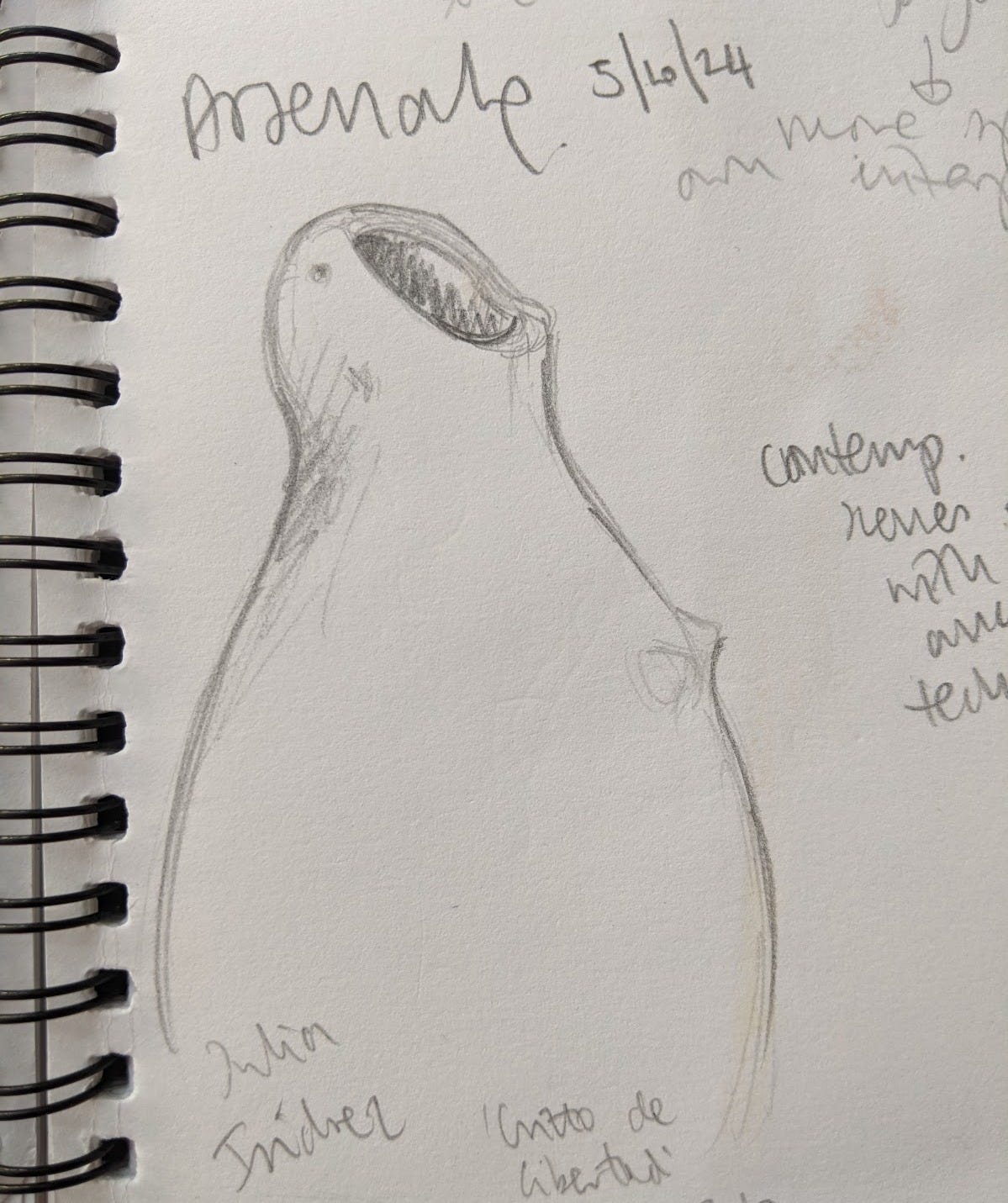

Julia Isidrez (born 1967) is a Guaranì indigenous artist from Paraguay whose work has developed from a centuries-long tradition of mothers teaching their daughters ceramics. Large, bulbous, playful, and full of life, her works question the relationship between form and function. I particularly loved her piece Grito de Libertad. Using a vase form as a starting point she transforms it into an anthropomorphised vessel that ‘cries for freedom’. However, before I translated the title, I did interpret the scream as a yawn, so viewers’ interpretations don’t always mirror artists’ intentions!

National Participations

Albania - Love as a Glass of Water

Albania’s National Participation presented the paintings of Iva Lulashi (born 1988) in a show called ‘Love as a Glass of Water’. The works were exhibited in a series of partition walls replicating the artist’s house, creating an intimate atmosphere, furthering the paintings’ themes of female intimacy and pleasure. The show’s title originates from the “theory of the glass of water”; the idea of a sexual and sentimental revolution where impulses are satisfied with the carefreeness that a glass of water is drunk with. After reading this introductory information I felt a little apprehensive, but I found Lulashi’s paintings beautiful and full of empathy for their subjects. With subtle colours and thoughtful compositions, they communicated a calming and nurturing female empowerment.

Senegal - Bokk – Bounds

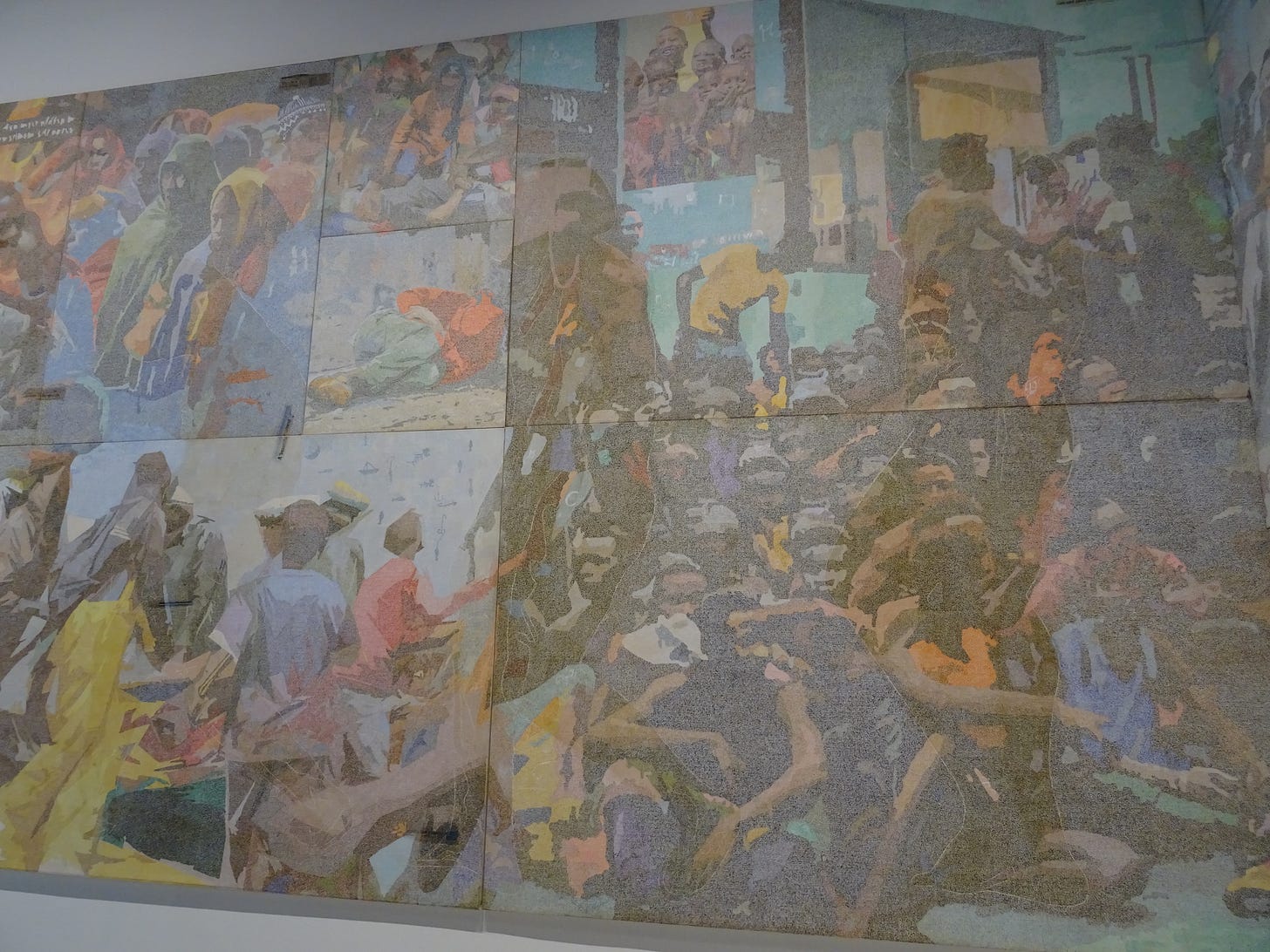

This year was Senegal’s first time exhibiting as a National Pavilion at the Biennale. They displayed Alioune Diagne’s (born 1985) work Bokk – Bounds. Stretching from floor to ceiling and spanning a width of 12 metres, this mural-like painting incorporated various scenes and panels to create one work. Diagne paints by clustering together small shapes to create a cohesive figurative image. The predominant imagery showed vibrant scenes representing education and community, as well escalating poverty and migration. This was subtly superimposed with the depiction of the famous March of Progress image of evolution, uniting the scenes. In the Wolof language, ‘bokk’ means “what is shared”. Here, Diagne depicts a shared humanity, a call to acknowledge the experiences of others, and uses an effective and unique painting style to do so.

Italy - Due Qui/To Hear

Italy’s National Participation, by Massimo Bartolini (born 1963), involved a series of installation pieces based around sound. The title of the work, Due Qui/To Hear, (Two Here/To Hear) is a word play welcoming us to reflect on how we listen to others. The principal work involved a dense and intricate scaffolding structure transformed into an organ. Set in the layout of a traditional Italian Baroque garden, it played commanding yet calming music that resonated throughout the large room. Where a fountain would typically be was a water sculpture: a circular wave pulsating with the organ music, its rhythm captivating. The mystery of how it functioned instilled viewers with a sense of wonder that felt peaceful and enchanting. After a long day of visual art, this was a rest for the eyes, a moment to experience art through another sense, hearing, and to exercise what we perhaps do not do enough, listening.

Glossary

*outsider artists are self-taught and untrained in the traditional arts, with no or little contact with the conventional art world

If you like what you read, please share this publication with your family, friends and fellow art lovers, and encourage them to subscribe too!

So good - love this summary. I also thought ‘love as a glass of water’ was particularly memorable too- I was really touched by it !

Loved this Maz! I found Misman's mosaic and Khalili's constellations particularly interesting.

I thought the use of censorship in the mosaic piece was somewhat ironic, as it's unlikely that you'd be able to identify anyone from a mosaic. I don't know what this could suggest? Also, protecting cultural heritage seems to be a fairly apolitical act (well, maybe not in Communist China, but still). Again, why the need for censorship?

As for the constellations - are constellations just an interesting visual parallel to a journey on a map or is there a deeper significance to the choice of a constellation?

Can't wait to read Part 3 :)