Tirzah Garwood: Beyond Ravilious

Rare opportunity to see the works of this playful and multitalented artist

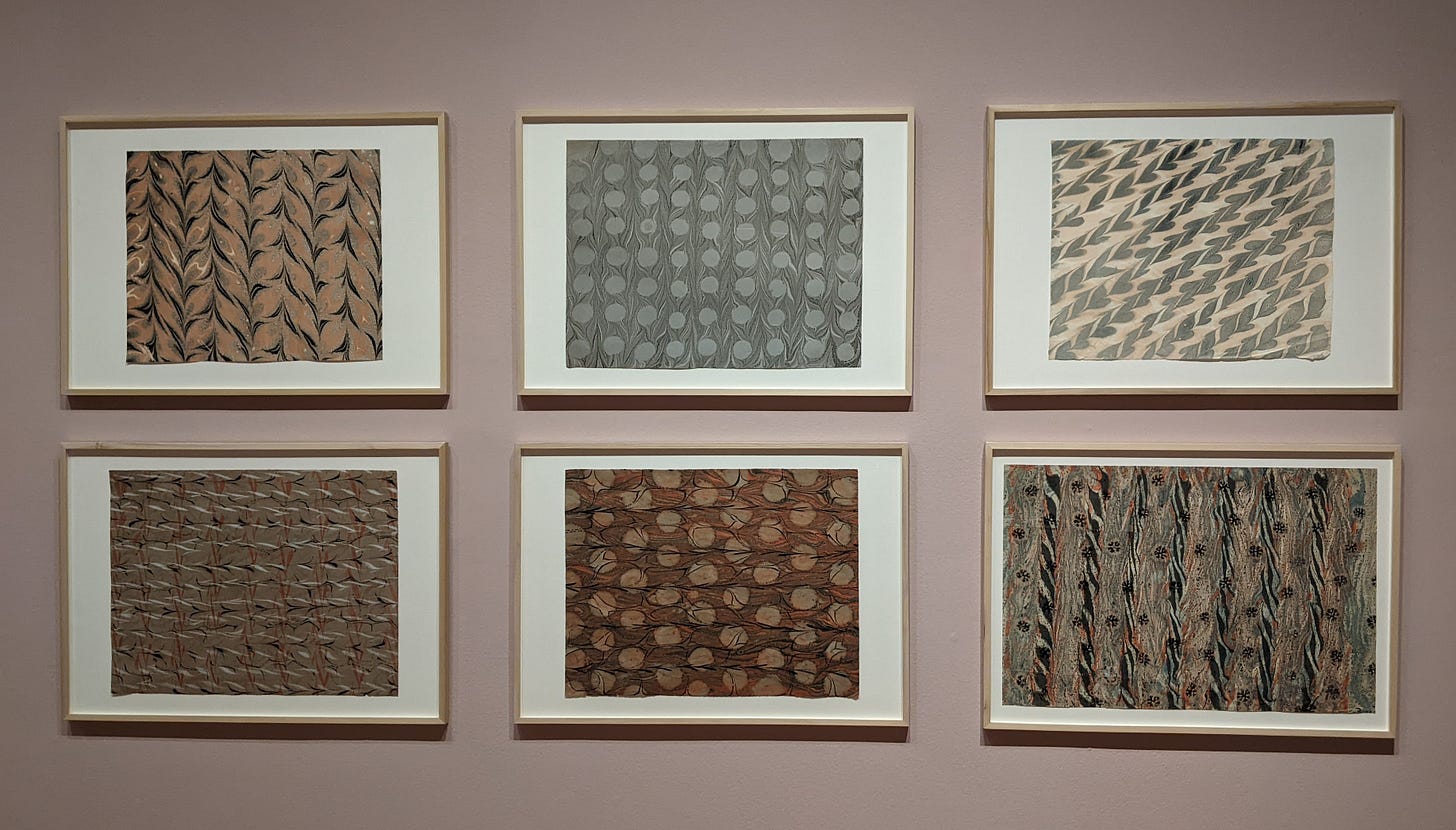

In its current exhibition (now entering its last two weeks), Tirzah Garwood: Beyond Ravilious, The Dulwich Picture Gallery presents a unique, joyful, and at times unsettling body of work by the 20th century artist Tirzah Garwood (1908-1951). Largely comprising works that have never been exhibited before, the show travels from engravings and oil paintings to scrapbooks, marbled papers, and cardboard houses. Garwood’s wide-ranging technical abilities are revealed and her youthful imagination becomes a common thread throughout.

Welcoming us to the exhibition are wood engravings from early in Garwood’s career. In Yawning, she portrays herself mid-yawn, showing her contorted arms and exaggerating the stretch of her open mouth. It is a snapshot of a mundane moment in which, despite the figure’s lethargic nature, we see an alive and vibrant creative individual. She is just waking up, embarking on the artistic career ahead of her.

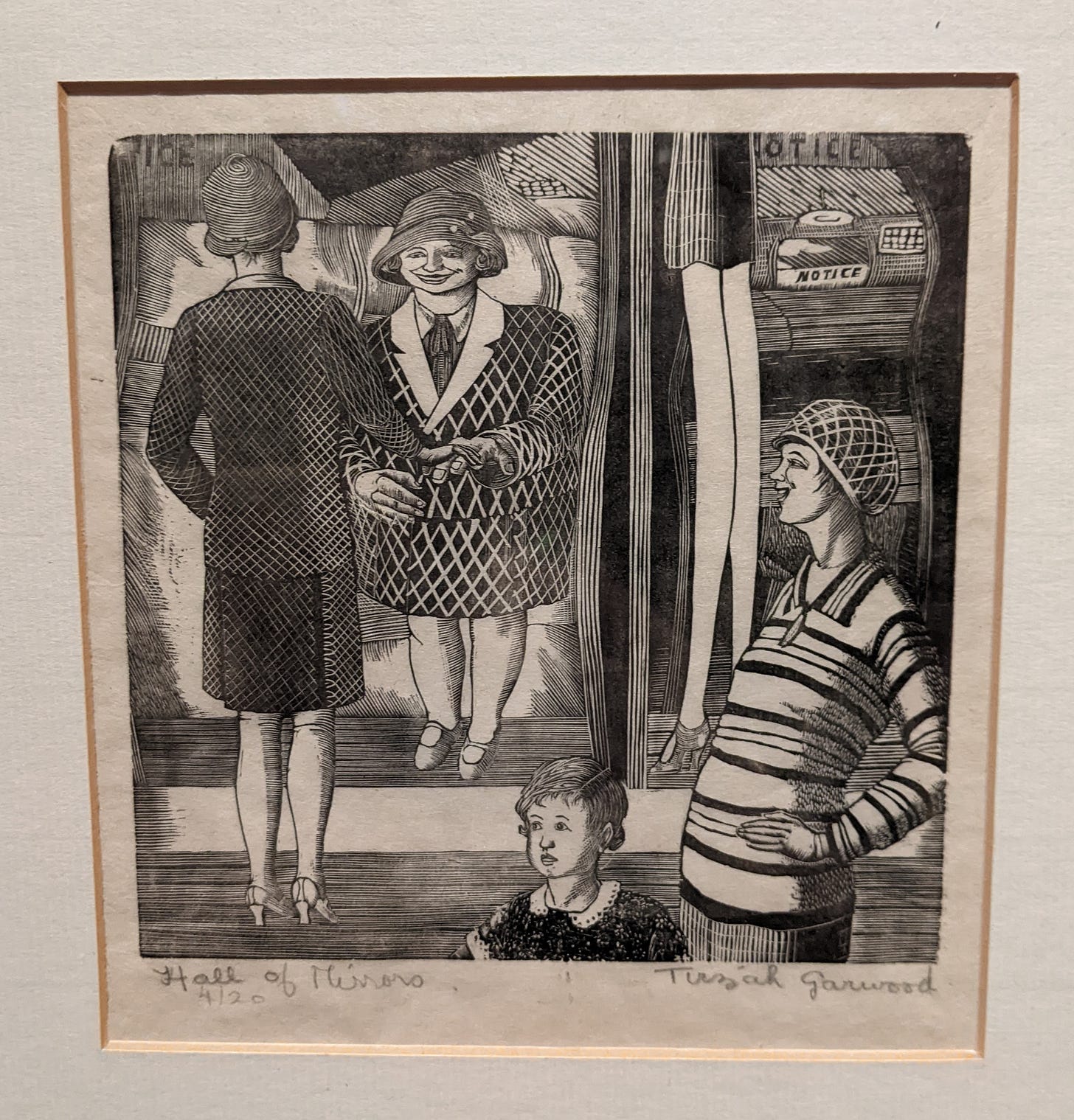

Similarly, in Hall of Mirrors, by emphasising the stretched criss-cross pattern of her skirt and jacket in her distorted reflection, Garwood presents a dynamic and playful figure. The Cheshire cat grin on her face, and the silent chuckle of the figure in the foreground, delight and entertain us.

Far from conventional, particularly when it comes to representations of women in the early 20th century, these precise wood engravings show great technical skill and demonstrate Garwood’s unique perspectives as an artist. She takes control of her own image, creating joyful narratives, that we can’t help but smile at.

Despite his name being included in the exhibition title, Garwood’s artist husband, Eric Ravilious, is not given much airtime in the show itself. His works that were featured complemented hers nicely. I wonder if the addition of his name in the title undermines the desire to go ‘beyond’ his influence, but I admire the gallery’s decision to not overemphasise Garwood’s gender. After briefly mentioning that her work has been overlooked, there was little virtue signalling about the status of women artists. Instead, a couple of facts (that her marbled papers sold for far less than her husband’s watercolours, and that she “lamented the impact” household chores had on her creative life) were casually shared and the viewer was left to make their own conclusions. Focus was on her works themselves and not wider social or political discussions.

The ‘flow’ between the rooms, the works, and the different pieces of information worked well. Information was spread across introductory texts for each of the three rooms, brief explanatory texts for some key works, and an audio guide including extracts from Garwood’s memoir. These latter autobiographical elements were not chronologically but thematically paired with the artworks. They helped to enrich the experience of the paintings, bringing the artist’s written voice to life, accompanying her visual voice.

The exhibition is the largest collection of Garwood’s house works since her memorial exhibition in 1952. These three-dimensional house ‘portraits’, celebrate subjects that both her and Ravilious would have enjoyed (she was mourning his death at this time) and were accessible for her children. They portray quaint village houses and shops, with lace curtains, well-tended bushes and garden fences. With front doors open, we get a glimpse of the house interiors, as well as the people, pushchairs and dogs that inhabit them.

Set in deep box frames, their three-dimensional nature is exaggerated, and we are invited into a little everyday world of delightful domestic details. Garwood uses a range of materials and techniques to achieve a multitude of effects and textures. In House at Night she uses corduroy material to depict a fence, whilst in Papermills, the trees and vegetation are printed from real leaves. Here, she also includes a working Meccano mechanism, moving the ducks along the river in front of the house. She focuses on key details that give the houses their character and differentiate them from others, such as the lancet windows in A.G. Peaston, Wethersfield Shop. An interesting home fascinates her like an interesting face would a portrait painter.

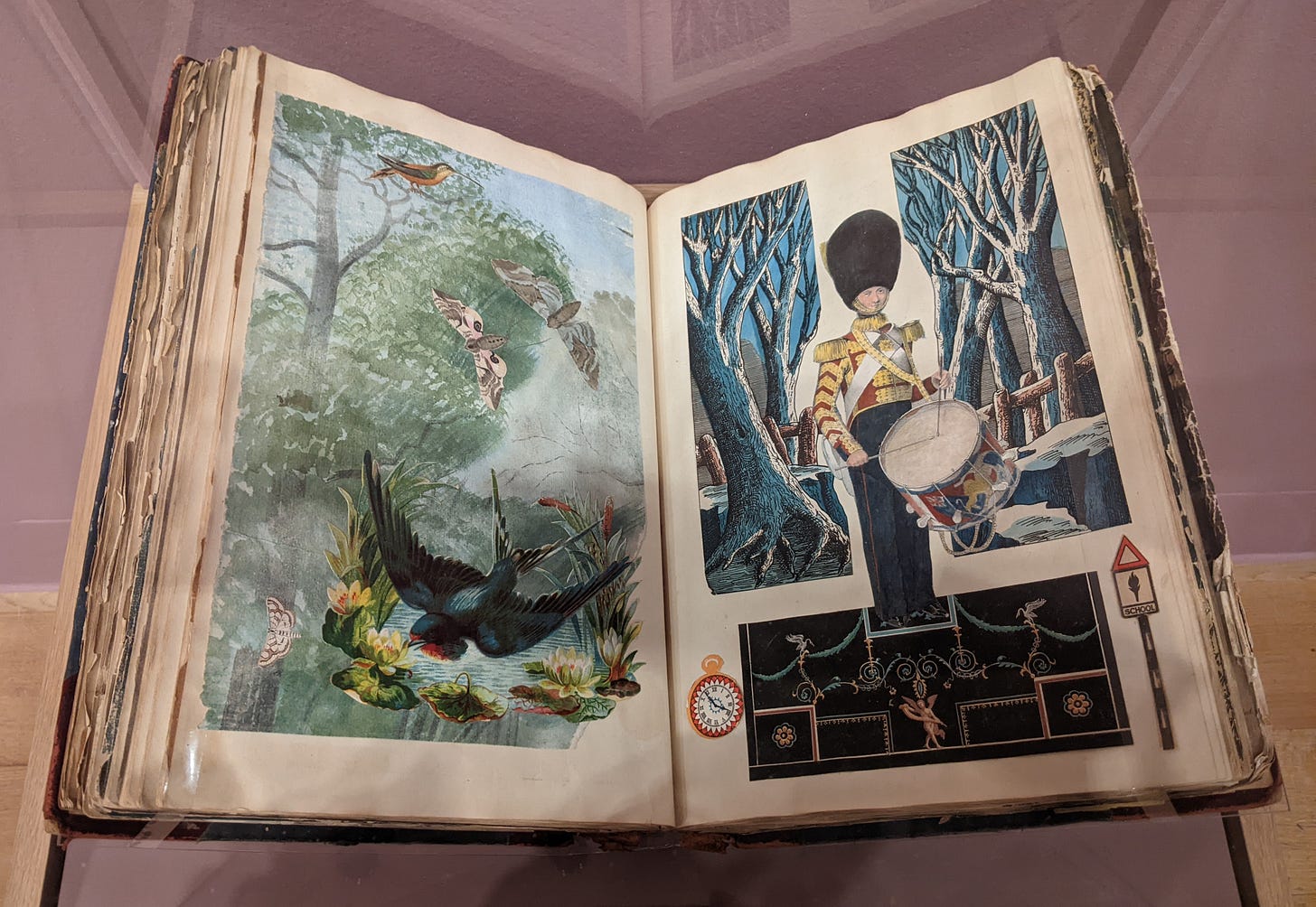

Garwood’s scrapbook was one of the most enchanting pieces in the exhibition. Filling the pages of this Victorian guard book* with collage, she juxtaposed artworks by friends and family, cuttings of Victorian illustrations and various memorabilia to create fantastical scenes - unique and surreal compositions. It was a thick, ornate tome. As incongruous as it was charming, the book included some of her own marbling papers, as well as Ravilious’ watercolours left unfinished at his death – a poignant addition to a marvellous family project and celebration of creativity.

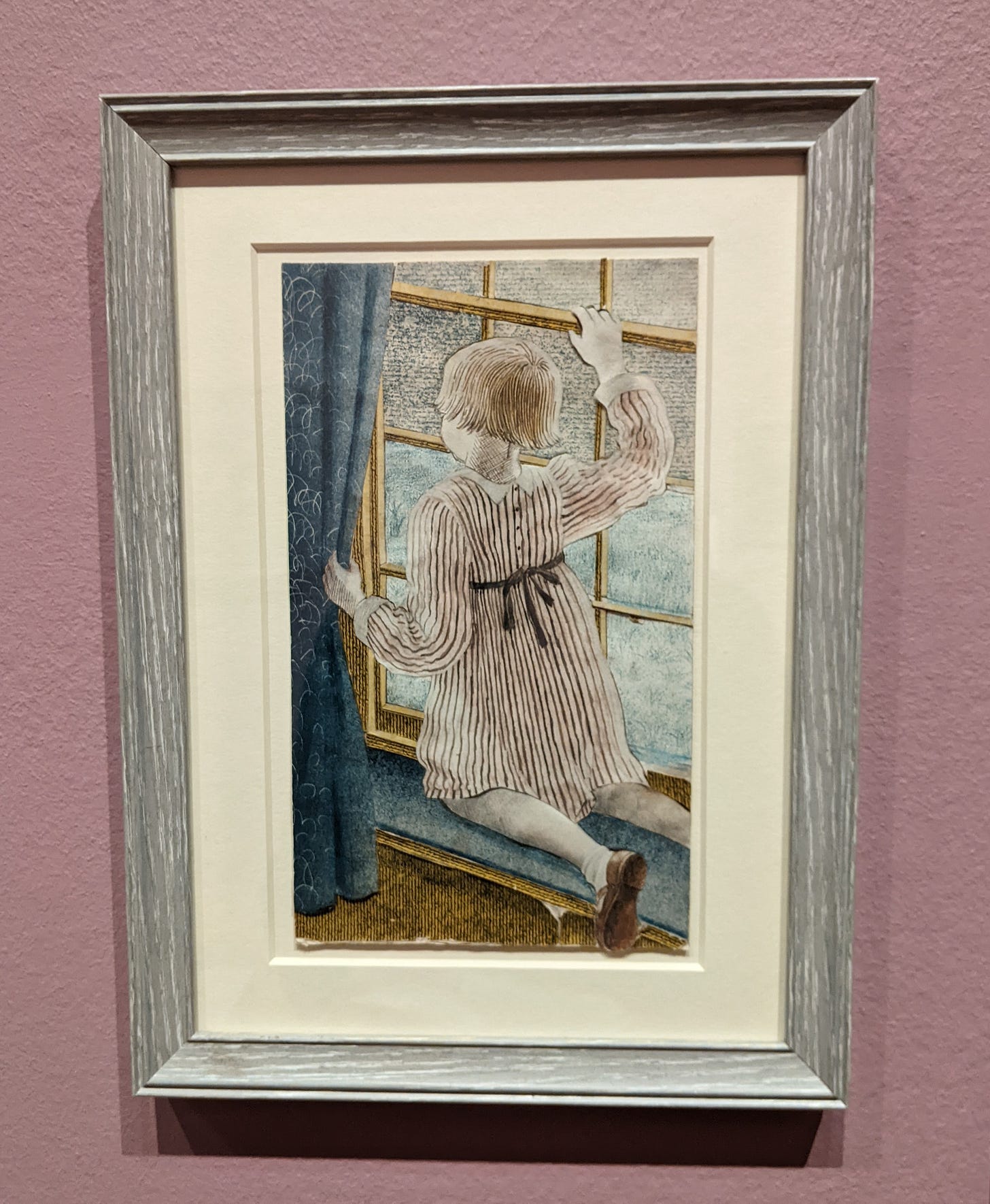

I found Garwood’s Portrait of Anne Ravilious (her daughter, aged three) instantly endearing. A collage of her own painted pieces, it simply but effectively conveys varying textures. With affection, she portrays the curiosity and wonder of a child peering out of the window. A sense of the expansive world of a child’s imagination and the life before her is conveyed. The child’s world goes beyond that of the window, just as her foot is allowed to delicately fall slightly outside of the picture’s edge.

In her oil paintings, Garwood uses a ‘sophisticated naïve’** technique to portray simple narratives that are appealing to children but have darker undertones. In her oil paintings of toys and animals set in nature, she looks at the world from close quarters, taking the viewer down to eye level with the grass, animals and toys. Blurring the lines between the real and the imagined, they have an uneasy, eery quality to them. Garwood perceives personalities in inanimate objects, creating the impression, as a sign in Garwood’s friend Peggy Angus’ house said, that “the simple life is more complex than you think”.

In Doll’s House Room, the artist depicts herself and her second husband, Henry Swanzy, as dolls. Though it is brightly coloured and somewhat humorous, the work also has a more sombre element. By this time, Garwood’s previous cancer had returned and she was increasingly confined to her bed. Through this work, she may have been grappling with her decline in health and the way that the world felt increasingly small around her.

The final year of Garwood’s life was spent receiving cancer treatment at a nursing home in the Essex countryside. The last room of the exhibition contains almost all her paintings from this year. Despite her illness, Garwood described this as the happiest year of her life, and, inspired by the nature around her, was prolific in her oil painting. In Springtime of Flight she expresses her joy in the flowers and open scenery, whilst reminiscing about watching “one of those early flying machines” with her mother as a child. We see a painter content with her life and eager to express its joys, despite the darkening clouds of illness above.

The exhibition’s final painting, Spanish Lady, depicts a ceramic Victorian water jug in the shape of a tall woman, set in starry, flower-filled scenery. Garwood meant it as a self-portrait, not least, the elongated neck resembles her physique. She has transformed herself into clay, serenely poised amongst the surreally ginormous flowers. The night sky and owl bring a sense of magic and the two dark spots for her eyes mirror those of the owl. She depicts herself in harmony with nature and a mystery that suggests she sees more than we do. Painted during the full severity of her illness, she gazes out to us, her expression slightly sorrowful but defiant, she is submitting to her fate. As the world closed in around her, it seems her internal world opened wider, her imagination more fruitful than ever.

This is the last in her series of inventive self-portraits that book-ended her career. In journeying between them, The Dulwich Picture Gallery successfully presents us with a holistic view of Garwood; an artist skilled in a variety of media, who takes us from the playful to the eerie, and presents a unique vision of the ordinariness of life that may not be so simple after all.

Tirzah Garwood: Beyond Ravilious is on at the Dulwich Picture Gallery until Monday 26th May.

Glossary:

* a guard book is a scrapbook or album, often used to archive published advertisements, and prepared with sewn-in guards for attachment of material. They were most prevalent from the late 19th century to the mid 20th century.

Scrapbooking had been a popular Victorian past time and then was revived in the 1930s.

** naïve art is simple and unrefined (though often detailed) and characterised by a childlike execution and vision.

If you like what you read, please share this publication with your family, friends and fellow art lovers, and encourage them to subscribe too!

I wish I could see this exhibition.

It was a beautiful exhibition, and extraordinary that Tizah mastered so many different mediums.

I saw it twice. The first tine I visited, I chatted with one lady who'd been to see it seven times. I expect she's seen it a couple more times since!