'Francis Bacon: Human Presence'

Last few days to see absorbingly intimate exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery

In Human Presence, the National Portrait Gallery depicts Francis Bacon at his most vulnerable, filled with sorrow and questioning. I left this show with a deeper understanding of and respect for Bacon, and one question at the fore of my mind: does a good portrait have to involve a recognisable sitter?

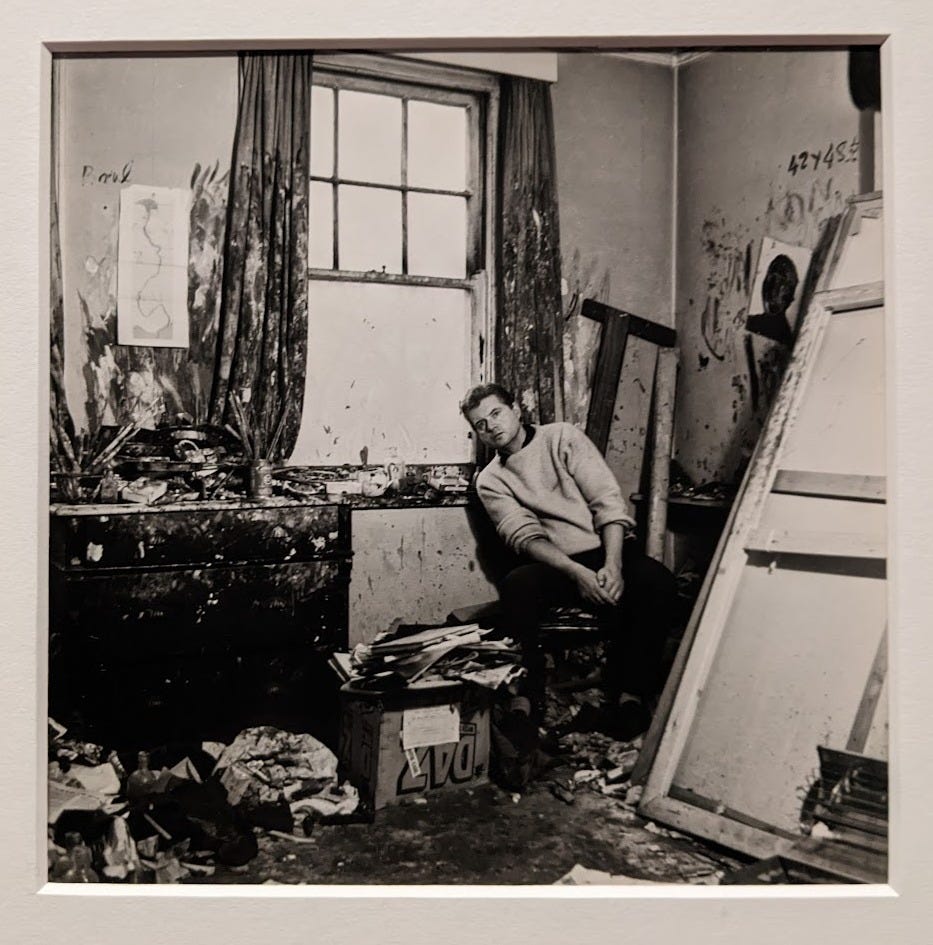

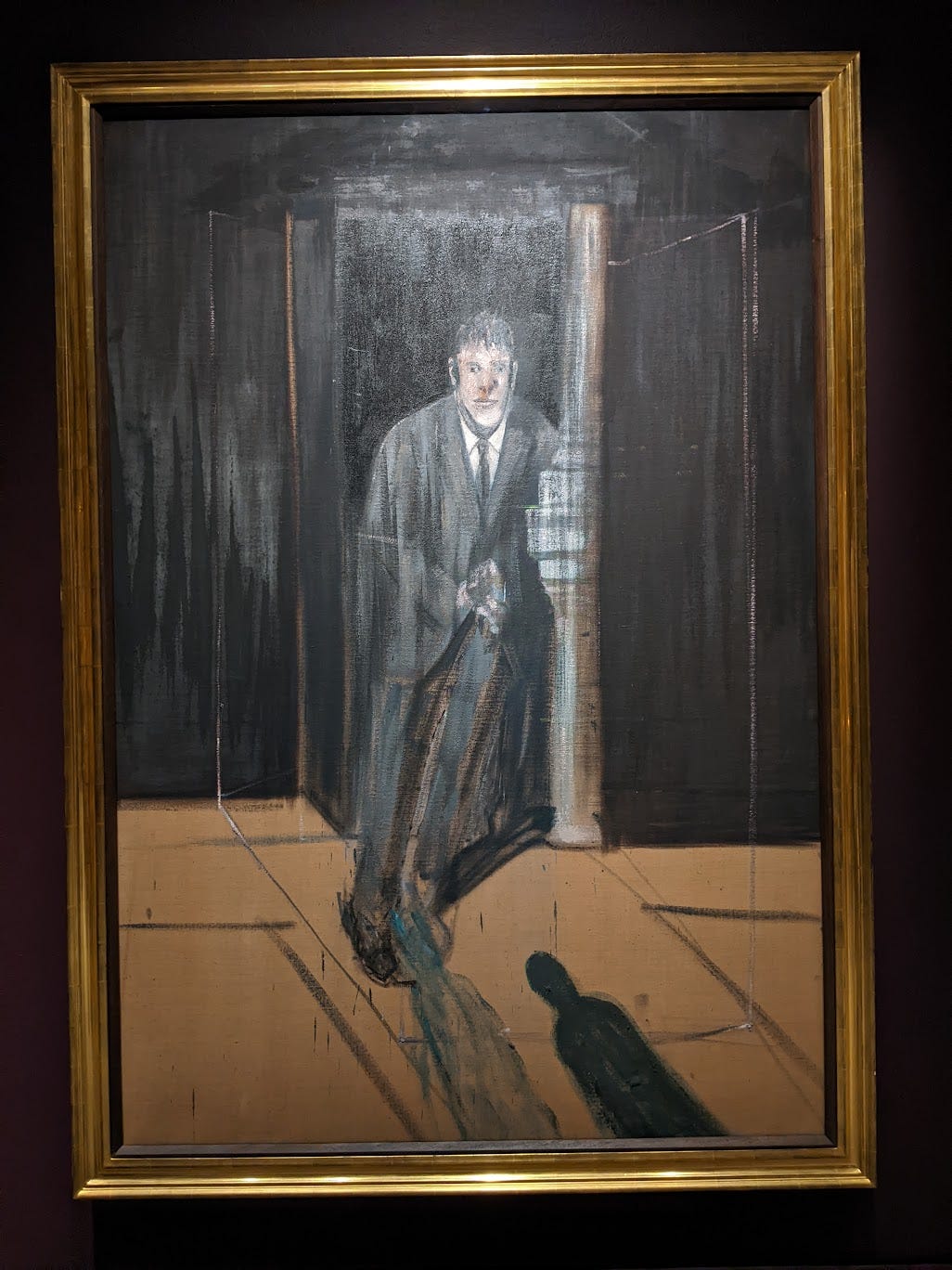

Francis Bacon (1909-1992) was a painter who, having never attended art school, developed a unique figurative style characterised by unsettling figures and distorted forms. His work is often heavily associated with the mood of post war Britain – a society grappling with the realities of human evil shown in the terrors of the Second World War. But this exhibition succeeded in showing the more personal side of the artist.

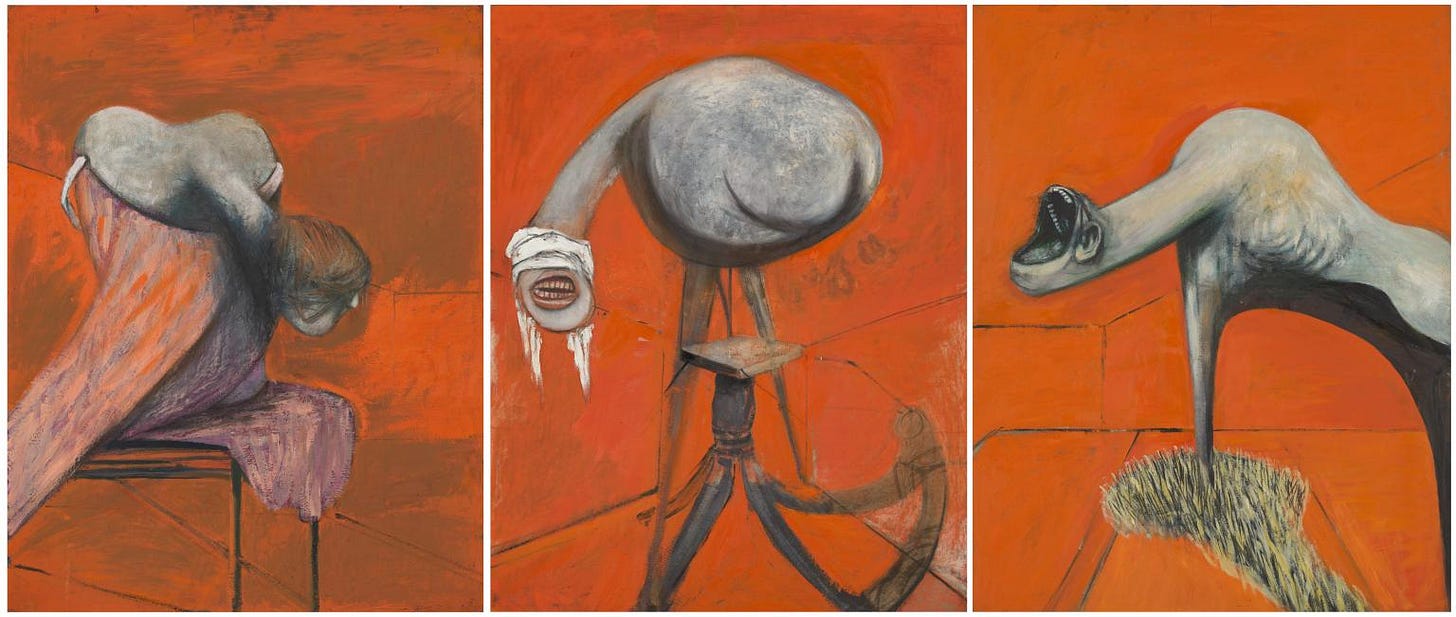

Studying him in sixth form, for me, Bacon was a catalyst for a deeper understanding of art (and life in general). I studied his Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion (on show for free at Tate Britain) and initially found it repulsive. But learning about it became an invaluable lesson in understanding others and how we all see the world differently. Through spending time with this painting, I realised that art isn’t (just) meant to be pretty but can give the viewer an insight into how someone else views life.

(Bacon often included the words ‘Study for’ in his titles, an ambiguous term that leads us to question whether the portrait is fully realised.)

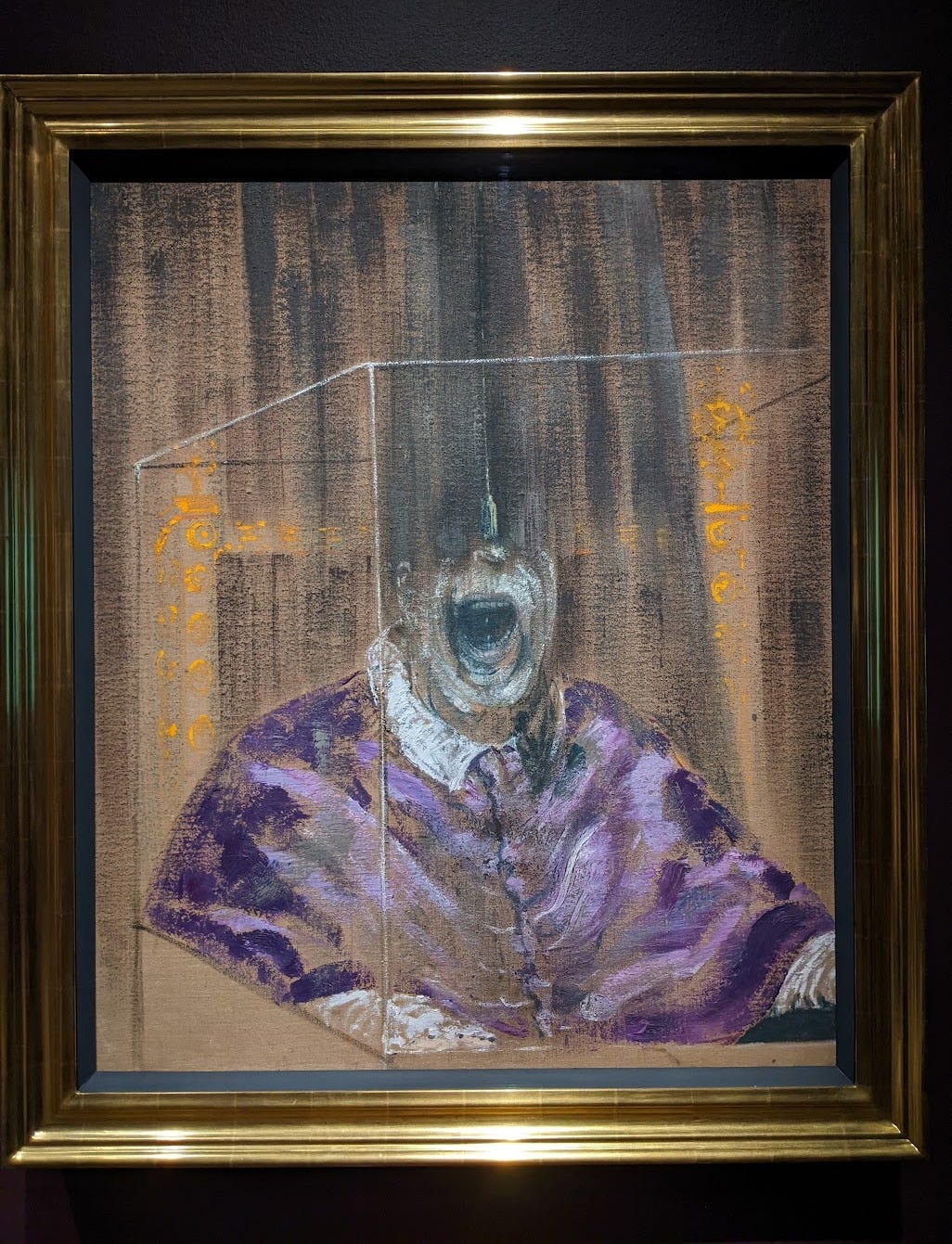

One of the first works in the exhibition was Head VI. It is Bacon’s version of Diego Velázquez’s (1599-1660) 17th century masterpiece Portrait of Pope Innocent X. Using a magnificent purple expertly offset from the brown canvas, he distorts the figure to beyond recognition, takes him from his throne and places him in an airless transparent cage, and strips him of his power and dignity. The traditional portrait format has been subverted. The head of the Catholic Church is terrified. And a small tassel tickles his nose.

Bacon made a number of what he called ‘distorted records’ of Velásquez’s portrait and admired several other masters. The exhibition also included his works inspired by Van Gogh’s The Painter on the Road to Tarascon. For me, these paintings weren’t so effective, their compositions were too busy. They seemed less intentional than his depictions of more solitary figures, where the lack of clutter creates a psychological intensity.

Despite this, it was fascinating to see how obsessed Bacon became with these works of previous masters. Here, the dialogue, the artistic ‘exchange’ across generations, from artist to artist, is on display. Interestingly, Bacon never saw these works in real life, only through reproductions. This pictorial distance perhaps gave him space to make his own mark on the figures. Alongside these, Bacon had a whole myriad of influences, such as book illustrations and film stills. These combined to produce a very unique style of painting.

Such were the many influences on Bacon that his portraits were often combinations of identities, not just representations of one individual. Lucian Freud (a painter and close friends of Bacon’s) arrived for sittings for his 1951 portrait to find that it was almost complete already. Bacon had used a photograph of the writer Franz Kafka as a reference. He found the presence of his subjects in his studio unsettling. Preferring to paint people he knew very well, he could conjure the essence of them without having their physical presence before him. The exhibition included a video interview where Bacon revealed that his sitters saw the distortions of themselves in the portraits as “injuries” and that he didn’t “want to practise before them the injury that I do to them in my work. I would rather practise the injury in private.”

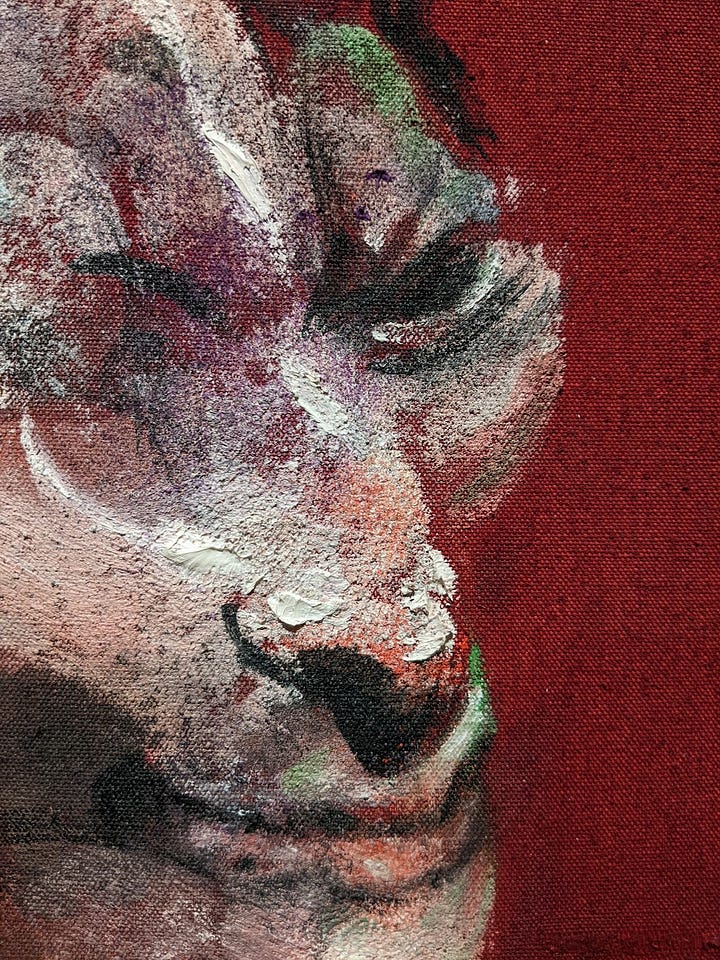

Bacon wanted to get across “all the pulsations of a person” and in doing so, used a wide variety of different brushstrokes and thickness of paint. His paintings included anything from chunky impasto*, to aerosol spray paint, to bare areas, showing the rough brown canvas underneath. In Portrait of George Dyer Riding a Bicycle the white paint is poured onto the canvas such that it appears sculptural. One of the many advantages of seeing artworks in real life is that we can get up close and experience these elements; we can feel their tangible presence.

The second half of the exhibition was dedicated to Bacon’s portraits of a small group of lovers and friends. These works heavily evoked his feelings for the subjects and associated memories. To achieve this, he used innovative approaches, such as in Three Studies of Isabel Rawthorne, where he represents her in three different poses across the canvas. In Portrait of George Dyer in a Mirror, the artist refers to the deterioration of his relationship with the subject (Bacon and Dyer had had a tumultuous love affair). Dyer’s face is severed from his head but appears in a mirror, where it is torn apart again.

The final work of the exhibition is also a portrait of Dyer, and an especially moving and haunting one. Though Bacon disliked narrative readings of his works, this is an exception. It’s a monumental triptych** showing Dyer taking his own life through a drugs overdose in a bathroom in a Parisian hotel room. The shadow of the central figure takes the shape of a bat, a devilish, consuming form. Dyer’s body is contorted in moments of anguish, framed by a sparse hotel room and accompanied by two arrows that add an element of clinical specificity. With great poignancy, Bacon depicts Dyer at his most vulnerable, and exposes his own sorrow and guilt.

This portrait is a harrowing end to a whirlwind exhibition. This isn’t simply Bacon’s horror show but an artist exploring the complexities of human emotion and despair. He takes us to the very depths of our existence, lays bare his own fears, and produces works that feel cathartic and oddly hopeful.

Francis Bacon: Human Presence exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery, London, closes this weekend – Sunday 19th January 2025.

Glossary

* impasto is a technique of layering paint on thickly so that it stands out from the surface.

** a triptych is an artwork that is split into three panels or elements

If you like what you read, please share this publication with your family, friends and fellow art lovers, and encourage them to subscribe too!

Wow! This is deeply moving Mary.

I knew/know so little about Bacon, but someone mentioned his work recently comparing his style to the that of Berlinde de Bruyckere’s ‘City of Refuge III’ exhibition on San Giorgio Maggiore(Belgium representative for the Biennale). I thought it was quite timely that this article popped up about a week later - so I wanted to read it to make the comparison for myself.